The NET Bible

Innovating from Digital to Print

By Nikki Getman

“You work in Bible publishing?” he asked when I told him my line of work. “There can’t be much that’s new with that.”

¶ I can’t fault him. After all, the Bible has been around for a couple of thousand years and has already been extensively published in multiple languages. I can see why my new acquaintance assumed there couldn’t be “much that’s new” in Bible publishing these days.

¶ But nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, the Bible has long been a key player in the technologies that surround the ways humans consume written material, and it remains so today—from inspiring advances in design to driving early adoption of innovations in how written content is produced.

The Bible driving innovation in publishing

An early example of this can be found in the codex (the precursor to the modern book), which emerged around the time Christianity was born. Up to that point, the scroll was far and away the most popular vehicle for written content. But early Christians were quick to adopt the codex, seeing in this new format a much better way of storing, sharing, and interacting with the collection of sacred books that make up the Bible. While a scroll was relatively easy to make, it was ill-suited for longer works. Nor was the scroll convenient for comparing passages, something Christians were eager to do, considering the New Testament’s frequent references to and interactions with the Old Testament. The Bible made full use of the codex’s improvements in space efficiency (by using both the back and front of the pages) and content organization. The early Christians’ emphasis on reproducing and sharing the Bible helped drive the codex’s popularity such that by the sixth century the new format had completely supplanted the scroll in the Christianized Greco-Roman world. *

¶ Fast-forward to the mid-fifteenth century when Gutenberg developed the breakthrough technology of metal movable type. His printing press revolutionized the speed of book production, giving unprecedented numbers of people access to information. The Reformers, with their emphasis on making Scripture available to all people, took full advantage of this technology and used it to spread their message far and wide.

¶ In the five hundred years since Gutenberg, all manner of styles and types of Bibles have been produced by many publishers. Today, Bibles are printed in a wide range of text sizes, column designs, with and without cross-references, study notes adjacent to the text, note-taking space, and a plethora of other tools and features—all of them intended to help readers engage with the text.

¶ The Bible’s very nature as an extremely large collection of books, combined with the way Christians tended to reproduce, share, and study the text, made it a driver for publishing technology. The challenge of collecting that many words in a truly useable format made advances like the codex or the printing press especially welcome.

¶ Even so, Bible publishing remained bound by the constraints of the physical print format. Despite advances such as the codex, or thinner paper, or innovations in typographic design, Bibles still present a special challenge for publishers. How many words can fit on a page without compromising readability? How many pages can be added to a book before it’s no longer practical to carry around?

¶ But with the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, two things happened: widespread access and limitless content. For a work as long as the Bible paired with the drive of an evangelical faith, this was an ideal scenario. And today, in a surprise twist, we’re seeing digital technology driving print innovation for Bibles.

* Alan Jacobs, “Christianity and the Future of the Book,” The New Atlantis, Number 33, Fall 2011, pp. 19–36.

A Digital NET Bible Full of Notes

In 1995, some developers who owned the web domain Bible.org sat down for an impromptu discussion with several renowned biblical language scholars, including Dr. W. Hall Harris, Dr. Daniel B. Wallace, and Dr. Darrel L. Bock from Dallas Theological Seminary in the lobby of a Philadelphia hotel during the annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society. Their conversation turned to how they could make the Bible freely available globally, and they quickly realized that no English translations available at the time were suitable for the task. The short list of public domain English translations, such as the King James Version (KJV) and the American Standard Version (ASV), used language that wasn’t as accessible to most modern English speakers. And licensing copyrighted modern translations for worldwide free use was cost-prohibitive. They decided to develop their own translation.

¶ By itself, this seems like a big job—but not necessarily a huge breakthrough. After all, there were already so many translations. But this committee made two pivotal decisions that could only happen in the digital age. First, they decided to apply a software-inspired approach by releasing beta versions of the translation. Starting in 2005, they invited worldwide comment on their work, which was brought back to the scholar committee for review. They received over a million submissions, helping them vet their work against error and bias. Second, since space was not an issue in their digital environment, they decided to keep extensive notes on their translation decision process, nearly verse by verse, and in some cases, word by word. The scholars not only defended their choices in these notes, but often explained why other translators over the centuries had made various other choices.

¶ In the end, the scholars of this project—which became the New English Translation, or NET Bible—documented more than sixty thousand notes—well over a million words. The result is not only a solid Bible translation, but unprecedented transparency into the Bible translation process and a stewarding of several centuries' worth of translation scholarship.

¶ This created an unexpected challenge for the Bible.org team, though. After release of the digital edition online, they began receiving requests for print editions of their translation—with the translators’ notes. Because the primary concern had been documentation unbound by the traditional space restrictions of print media, packing all those notes into a useful and workable format was a special challenge.

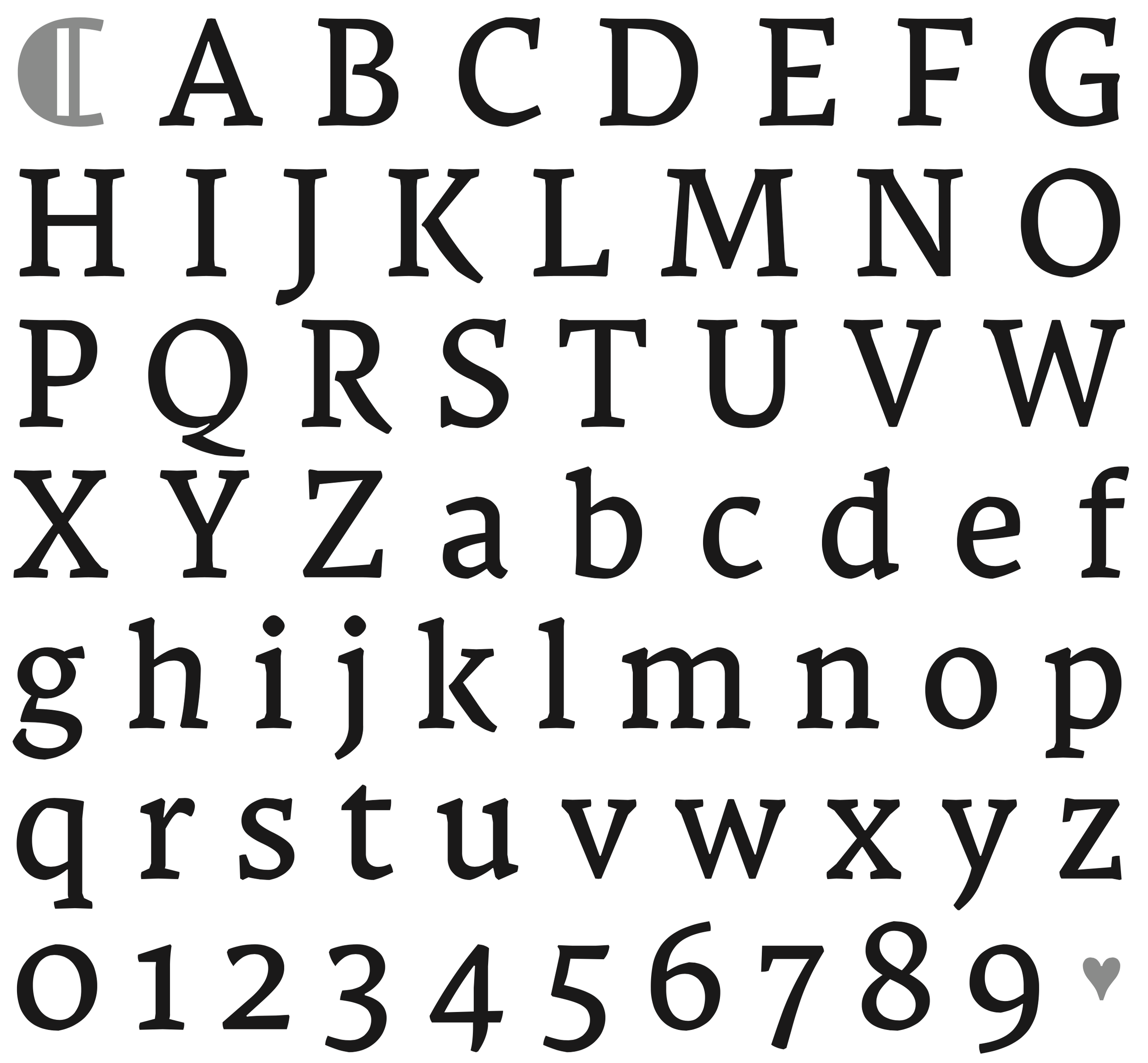

TN NET Serif Regular is the main typeface in the TN NET typeface family consisting of Serif Regular, Serif Italic, Serif SemiBold, Serif Semibold Italic, Sans Regular, Sans Italic, Sans Semibold, Sans Semibold Italic.

The limits in print requires innovation

At Thomas Nelson, we appreciated the contribution the NET made to Bible translation. For over 200 years, we have been publishing Bibles in the King James Version stream of Bible translation. Many people may not realize that the early editions of the KJV in the 1600s included thousands of translator notes where the original team provided short discussions about translation choices and listed possible alternative choices to help readers gain insights into the meaning of the original text. This approach to the translation was a choice that informed Thomas Nelson’s twentieth-century development of the New King James Version, which footnotes possible variants and ancient manuscript differences. To us, the NET is the twenty-first century’s continuation of that open-handed view of biblical language scholarship.

¶ At the same time, we knew from all of our experience that the scale of the text would be difficult to contain in a manageable print format. Some of the more difficult or complicated sections of the Bible could have hundreds of words of commentary per word of Scripture text, while other passages whose meaning is fairly uncontested might have very few notes. There was only one place to go to come up with a world-class solution: 2K/Denmark.

¶ For the last few years, we have relied on the 2K/Denmark team to develop translation-specific typefaces. More than anyone, they understand the unique requirements of Bible typography, and their innovations in typographic design allow Bible publishers to maximize the readability and beauty of the text while reducing the space required to hold all of the text. We were excited to send this project to them because we knew they would insist on developing an elegant solution.

¶ I will never forget when we saw the first design recommendations. We see so many Bible designs come through, and they are usually iterations on well-worn page layouts. Their solutions were strikingly different and yet grounded in historic Scripture design. The standout was a page design that brought the reader’s focus to a single column of semibold Scripture text wrapped on three sides by columns of commentary in a slightly smaller size and a dark gray color. The sheer amount of notes could have overwhelmed and overshadowed the Scripture text, but the effect of 2K’s innovative layout, as well as the weight and color of the different components, is that the Bible text’s primacy remains clear even as the notes are made remarkably easy to read. The design is a modern take on a Jewish Talmud design from about 2,000 years ago, and also references medieval illuminated Bibles.

¶ Another impressive decision the 2K team made was aligning the Scripture text at the top of the page, and then filling the commentary columns from the bottom of the page. This approach allowed them to line-match both the Scripture text and commentary so that when the pages are printed back-to-back on the thin Bible paper, there is minimal show-through and optimal readability. Each of the 2,400 pages in the final edition was carefully built for appropriate breaks in the Bible text balanced with the amount of notes matched to them.

The best job

It’s fun watching people experience this Bible for the first time. They usually start out skeptical, wondering why they should care about a new translation. But when I present them with this beautiful, innovative copy of the NET, they’re immediately drawn in by the stunning combination of readable Scripture text and the unique presentation of an unprecedented number of translators’ notes that make the Bible come alive for the modern reader. They begin turning page after page, stopping to read, and then turning another page for more.

¶ And that brings us full circle. The unique challenges of the Bible—its length, the requirement of portability, the need to be readable and understandable for all people—continues to drive innovations in the world of written content, from print media to the digital world and back again.

¶ With this project, conversations about the work I do in Bible publishing usually end with, “You have the best job!” And I agree.

Nikki Getman is marketing v-p for the Thomas Nelson Bibles team, a division of HarperCollins Christian Publishing. She has spent over 20 years connecting people to life-changing content.